Metro Cable Project

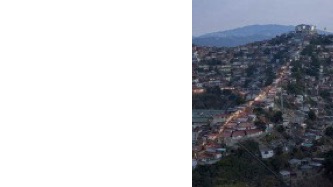

Metro Cable Project

In July of 2003, UTT organized an informal, but very public, presentation and symposium at Caracas’ central university to protest the government plan and begin the process of exploring alternatives. Attended by architects, planners, various other experts, university activists, and barrio leaders, the meeting stunned government planners: speakers from San Agustín were not only vehement in their objections, they were eloquent and well-informed. In rejecting the plan, they also articulated very specific demands, among them the preservation of a pedestrian-oriented community; mixed-use development; expanded parks, and attractive, safe streetscapes; sources of employment, including entrepreneurial opportunities; and various other community amenities.

This was a watershed moment in land-use planning and development: never before had a “slum” community asserted the right to shape its own future; never before had stake-holders demanded a role in the decision-making. The government backed down.

More significantly for the ensuing exploration and planning process, the symposium resulted in the creation of a task force consisting of an organized group of community volunteers and the UTT team. In relatively short order, the task force selected from among several alternatives the cable car system as having the greatest potential: ideally suited to the terrain, minimally invasive into and destructive of the existing fabric, highly sustainable, and flexible.

A Connect-the-Dots System

The idea of the a MetroCable has been proven and tested in Barrios in Medellin, Colombia, but what is more here is that the MetroCable Stations provide more than just transport but are hubs for social services and other community activities.

Though the five stations share in common a basic set of components and designs – platform levels, ramps for access, circulation patterns, materials, and structural elements – they differ in configuration and the possibility of additional functions that address other community needs. While not all of these additional purposes are being constructed at this initial stage of the project, the opportunities of integration of the stations with the community include:

– The San Agustín and Parque Central stations, at the base of the hillside, include social, cultural, and system administrative functions.

– At Los Mangitos, 40 units of housing will be built, replacing homes whose demolition is an inevitable necessity for station construction. The station structure also includes public spaces for community gatherings, out-patient health care facilities, and other similar amenities as well as a playing field on top.

– In addition to the station itself, the La Ceibita site has a second structure that links the station to ground level, 16 meters below, and includes a gym and government-sponsored supermarket and day-care center. The station is also connected to an existing housing complex and to a roadway with a municipal bus stop.

– Hornos de Cal, the third of the ridge-line stations, affords unique opportunities, as it is the least-densely developed neighborhood and offers the planners more space to work with. It is also the site of a large water tank, which has long been a barrio icon of sorts. The tank will be demolished and the station built on its foundations, taking the tank’s place both literally and symbolically: the new station is intended to function as a beacon and look-out tower with a viewing platform, from which all of Caracas can be seen spread out in the valley below. The development of this site also includes the restoration and expansion of an existing soccer pitch and the implementation of a major open-space and streetscape plan.

This connect-the-dots scheme has the considerable virtue of being minimally invasive of the community fabric, weaved into it only at five discrete points. The hilltop stations, set into densely-built neighborhoods, rest on stilts to avoid all but the absolutely essential demolition of homes. Like the gondolas themselves, the stations float above the ground, a near-perfect expression of an ideal intervention: one that facilitates and connects without imposing, that emerges literally and figuratively from the community it serves.

Plug In, Flow Around, Float Over

In addition to minimizing the impact on the built environment, elevating the stations above ground serves significant climatic and geographic purposes. Air-flow at pedestrian level is preserved, and adjacent homes continue to benefit from the cleansing and cooling effects of the prevailing winds. Erosion from the typically heavy annual rains is minimized, protecting the station structures themselves as well as the surroundings. And the stilt-like legs greatly simplify compliance with seismic requirements. Additionally, the structural support for the platforms and cable car system is independent of that for the station shell, which is thus unaffected by the inevitable vibrations from system operations and pedestrian movement.

The barrio-dwellers of San Agustín and of the rest of Caracas’s informal city live officially off-the-grid, though they can and do “borrow” power from municipal lines. The heavy rains notwithstanding, there is no supply of potable water. And residents make extensive use of recycling in the construction of their homes. Thus, all of UTT’s work in the Caracas barrios rests on the fundamental principle of sustainability. No project is of any value to barrio-dwellers if it relies upon resources beyond their means or reach or depends for its completion and operation on promises of future assistance. Moreover, key features of sustainability are at the heart of the community’s culture and way of life, making it vital for a project that has arisen from the community’s will.

The View From Here

A key criterion underlying the award to the UTT task force for the Caracas MetroCable project was the question from which our proposal arose: what kind of city do we want to see in 2025? Merely inquiring into the anticipated system capacity, for instance, made no sense. We recalled the lessons of the much-heralded Long Island Expressway in New York, obsolete before it was completed: you cannot “build for tomorrow” – you can only build in such a way as to be able to “build tomorrow.” Moreover, the changes underway in the informal city – in Caracas, as elsewhere – are not only extraordinarily rapid, they are truly transformational.

What we did seek, on the other hand, was to put in place the means for change in relation to the fundamental needs of the barrio of San Agustín, those its inhabitants themselves identified:

– Safe, accessible, and cost-effective public transportation for barrio residents

– The growth of work opportunities and of the economy of the barrios

– The development of a sustainable infrastructure to give permanence and stability to the community

– Improvement of the health, education, employment opportunities, and quality of life for barrio-dwellers

– Improved safety and reduction in crime

For UTT, we look forward to 2025, even earlier perhaps, with two particular aspirations: that the San Agustín scheme will be translated to other Caracas barrios, eventually effecting the physical, economic, social, and cultural integration of formal and informal cities; and that the empowerment of the barrio communities will be perpetuated and grow stronger, giving them permanent ownership of their destiny.

In April 2009, the first line going from Parque Central station up to La Ceiba was formally inaugurated. The completed Metro Cable system is expected to open in December 2009.

About Urban Think Tank

Urban-Think Tank is an interdisciplinary design practice dedicated to high-level research and design on a variety of subjects, concerned with contemporary architecture and urbanism. The philosophy of U-TT is to deliver innovative yet practical solutions through the combined skills of architects, civil engineers, environmental planners, landscape architects, and communication specialists. In 1993, Alfredo Brillembourg founded U-TT in Caracas, Venezuela, and in 1998, Hubert Klumpner joined as co-director. Since 2007, Brillembourg and Klumpner have taught at Columbia University, where they founded the Sustainable Living Urban Model Laboratory (S.L.U.M. Lab), and since July 2010, they hold the chair for Architecture and Urban Design at the Swiss Institute of Technology, ETH in Zurich. Their work concerns both theoretical and practical applications within architecture and urban planning. Working in global contexts by creating bridges between first world industry and third world, informal urban areas, they focus on the education and development of a new generation of professionals, who will transform cities in the 21st century. They have been awarded the 2010 Ralph Erskine Award from the Swedish Association of Architects for their innovation in architecture and urban design with regard to social, ecological and aesthetic aspects.

Metro Cable Project

- Authors: Urban-Think Tank

- Location: San Agustin- Caracas / Venezuela

- Year: 2003 > ongoing (built: 2007- 2010)

- URL: http://www.u-tt.com